“Be honest. You want to observe through the biggest telescope you can get your hands on. A statement by David Kriege, the author of the book “The Dobsonian telescope”, which aptly describes the phenomenon of “aperture fever”.

After I finished building several versions of a 45 cm f4.6 Newton. I could look back on ten years of trail and error, of designing and constructing. A ten-year obsession to create a large, yet practical, telescope. In the end I build four versions over the course of 10 years.

(click on the image to go directly to a version or scroll to the bottom of this page to follow the timeline and go to the next version)

2004 2006 2008 2010

Although the Netherlands has some reasonably dark areas, I don’t live there. So my telescope needed to be portable. By the end of the nineties ATMers in the US started building ultralight portable telescopes. Like a lot of amateurs I was fascinated by the 16 inch string telescope that Dan Gray build in 1999. In a radical attempt to reduce the weight of traditional aluminum tubes, this telescope has three pairs of strings which are tensioned by two carbon tubes. The advantages of this design are: a lighter secondary ring, fast setup and breakdown of the telescope and no complicated truss connections. This was the type of telescope I was hoping to build.

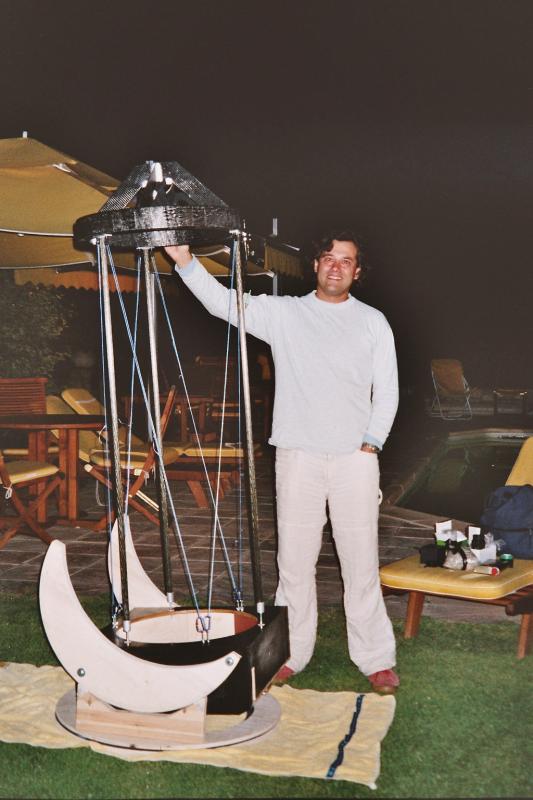

The first try

Having spend the whole of 2001 and 2002 drawing and calculating, construction on the first version of the 45 cm Newton finally started at end of 2003. The idea was to build a Dobson, but an ultralight one with strings instead of trusses.

Mirror box

The telescope had a 9 point mirror mount calculated with PLOP. The aluminium triangles were mounted on small composite bearings (IGUS) which in turn were fixed to a plywood plate. The plywood was reinforced with carbon as was most of the mirror box. This stiffened up the box substantially and made it possible to use mostly 9mm multiplex. Rollerskate bearings provided the lateral support of the mirror.  The top of the box was reinforced with a double layer of carbon to resist bending due to the forces exerted by the strings.

The top of the box was reinforced with a double layer of carbon to resist bending due to the forces exerted by the strings.

Strings

The strings in this first version consisted of 20 single threads per string (6 strings total). They were connected to the mirror box and the secondary ring with small carabiniers. I needed to keep the weight of the secondary ring low, which was difficult considering that the secondary mirror weighted 1kg and the focuser, eyepiece and finder added another 2 kg. The rest of the weight needed to be less than 1 kg. In the end the ring weighed a little under 4 kg. The secondary vanes where made out of 2 mm balsa wood covered with 4 layers of carbon. The ends where clamped in a ring of polyurethane foam sandwiched between two rings of 2 mm balsa.

Secondary ring

The ring was then wrapped with carbon band. This created a particularly light and rigid structure. Most telescopes constructed with a single ring have a focuser that is mounted below the ring. Following the example of Greg Babcock’s 24 inch Newton I chose to mount the focuser on top of the ring. The pyramid construction of the vanes is very stiff and has the added advantage of being able to use shorter tubes and strings. This also allows for the secondary ring to rest on the mirrorbox during transport. The secondary mirror was glued to the vanes.

Dobson mount

The side bearings where made of 30 mm plywood, ebony star was used as a bearing surface. The azimuth was constructed as a so-called flex rocker. Not 3 but 4 points are in contact with the ground ring. The telescope weighed about 27 kg and easily transported in a Volkswagen Golf with room for one extra passenger. The final result got first light in the summer of 2004 under a beautiful sky in the southern French village of St Michel l’Observatoire.